Home > Academia > DOMINICAN REPUBLIC - Building Trans-migrant Citizenship: International (…)

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC - Building Trans-migrant Citizenship: International Migration and Political Transnationalism

Edward D. Gonzalez-Acosta (New School for Social Research)

Tuesday 15 May 2007, by

Abstract

The central questions of this paper are: How is the concept of citizenship and nationality of labor exporting countries being expanded to incorporate their migrants living abroad? Through which political and cultural mechanisms is this occurring? And how is this process evident in the case of the Dominican Republic and its migrants living in the U.S.? To address these questions, I adopt a transnational model to the study of migration and political integration– instead of the more conventional assimilation or multicultural approaches. For my project transnational practices mean “sustained ties of persons, networks and organizations across the borders across multiple nation-states, ranging from little to highly institutionalized forms” (Faist, 2000: 189). I argue that the more traditional models to study migrations and political incorporation do not account for the transnational practices in which migrants engaged in, and which states and civil society organization promote.

By addressing the above questions, I intend to accomplish three goals: 1) provide a survey of the immigration and political transnationalism literature; 2) make the argument that this literature provides sufficient evidence to support the claim that migrants’ citizenship and nationality are becoming transnationalized in that citizenship rights, duties, and identity are being expanded beyond the nation-state boundaries; 3) and that this literature systematically focuses on migrants, local and national institutions (both in the sending and host countries), but excludes non-migrating individuals who are affected by migration and political transnationalism.

*

* *

In 2007, “the Central Electoral Board (of the Dominican Republic) and the Airports Department announced … the installation of offices in the airports to issue birth certificates and the electoral identity cards to Dominican citizens residing abroad [1]” (Dominican Today, 2007). In addition to facilitating the process of attaining birth certificates and registering to vote, the president of the Central Electoral Board also announced the opening of new polling stations in Holland, Milan, Zurich, and Washington D.C., where Dominicans abroad can vote; these are in addition to offices already operating in Canada, Venezuela, New York, New Jersey, Boston, Philadelphia, Puerto Rico, Madrid, Barcelona, and Miami (Dominican Today, 2007). These are some of the most recent endeavors by the Dominican state to facilitate the incorporation of Dominicans living abroad in Dominican politics and society. The Dominican Republic (DR) has a population of about 8.5 million and has approximately 1.5 million Dominicans living abroad, mostly in the US. In other words, 17.6 percent of people born in the DR live outside the DR (Suki, 2004). For its part, the IDB (2004b) estimates that over 2 million adults born in the DR are currently living or working abroad.

This paper analyzes the Dominican [2] experience of migration and political transnationalism to explore how the official concepts of citizenship and nationality of labor exporting countries are expanding in order to incorporate their transnational migrants into the home countries’ politics and society. This issue is important to study because it has wide theoretical and policy implications. Theoretically, the transnationalization of politics and the granting of rights and duties beyond the nation-state challenges conventional theories of citizenship that claim that citizenship is territorially bounded to the borders of the nation-state. Challenging these conventional theories can provide analytical tools to studying the political and social phenomena associated with migration and political transnationalism. Policy-wise, studying the mechanisms by which the state is expanding citizenship rights and duties, and the actors involved in this process of change can increase our understanding of the relationship between these state-led overtures to play on their transnational migrants’ loyalty and the sustainability of migrants’ transnational practices and links. This paper will engage, primarily the theoretical implications of this question. The policy implications are beyond the current scope.

I divide this paper into four sections. In the first section I provide an overview of different conceptions of citizenship and argue that citizenship is a concept that has been traditionally territorially-bounded to the contours of the nation-state. The second section engages with migration trends to the US, particularly from the DR, and describes some of the transnational practices that migrants engaged in. In this section I will briefly touch upon the four waves of immigration to the US. I will also briefly describe the importance of monetary remittances at the local and macro level. In the third section I will engage explicit efforts by the state and immigrant organizations to expand official citizenship rights and duties and the boundaries of the imagined national community to play on migrants’ loyalty to continue being involved in their home-country’s politics and society. Lastly, I will make the argument that conventional theories of migration fall short of explaining transnational practices and the creation of transnational-citizens, and that the transnational theories that actually tries to account for political transnationalism neglect non-migrating individuals in the home-country that are linked to immigration through financial and cultural exchanges.

The concept of citizenship has traditionally been a territorially bounded notion. It is an institutionalized form of solidarity between the state and its people, and a political and cultural tool that represents full and formal membership within a political community (Faist, 2000: 202; Smith, 2001: 73; Baubock, 2003: 139). “A citizen is, most simply, a member of a political community, entitled to whatever prerogatives and encumbered with whatever responsibilities are attached to membership” (Walzer, 1989: 211). There are several conceptions of citizenship; I will discuss two of the main conceptions: the liberal and the republican. The liberal conception of citizenship highlights the rights and liberties of individuals as members of a political community (Schuck, 2002: 132-3). The Republican conception, for its part, emphasizes the duties and civic commitments and virtues of members of a political community (Dagger, 2002: 147, 148-9; Stychin, 2001: 351-2; Walzer, 1989). These two conceptions of citizenship obviously center on different aspects - on the individual and on the republic, respectively - but both place citizenship within the territory of the nation-state. For both, citizenship is “a national project in which individuals in fact will transcend their particular affiliations, towards full and foundational membership in a wider community” (Stychin, 2001: 352). Smith (2001) is more explicit in arguing that modern citizenship (whether republican or liberal) “means membership in a large-scale republic that has boundaries roughly conforming to some partly pre-existing ‘national’ community, and it thus is a feature of” nation-states (p. 73).

Studies of citizenship usually start of by exploring T.H. Marshall’s three dimensions of citizenship: civil, political, and social. The Marshallian approach presents citizenship as the expansion of individuals’ rights: civil rights are those necessary for individual freedoms – these grant citizens freedom of speech, rights to fair trail and so on (Marshall, 1998: 94). Political rights provide citizens “political equality in terms of greater access to the parliamentary process. In this area political citizenship require the development of electoral rights and wider access to political institutions for the articulation of interests” (Turner, 1990: 191). Finally, according to Marshall, citizenship also grants citizens social rights in the form of claims to state welfare and entitlement programs to ensure social security in periods of distress (e.g. unemployment, illness) and old age. Marshall’s conception of citizenship rests squarely on the concept of the nation-state. There is a direct state-citizen link. The rights that are embodied in Marshall’s three dimensions of citizenship are granted and protected by the state and its institutions, and are associated to the nation-state (Faist, 2000; Turner, 1990).

From this modest literature survey, it is reasonable to claim that theories of citizenship have traditionally been used to demarcate membership in a spatially defined nation-state.

Turning now to theories of migration, there are many theories that attempt to explain why people decide to leave their home-country and migrate abroad. Three of the main theories of migration, are reviewed by Castle and Miller (2003) and Graham (1996); these are the Neo-Classical, Historical-Structural, and Migration System. These theories are not independent of each other, but they each articulate a different aspect of reasons why people migrate:

Box 1: Theories of Migration

| Neo-Classical – This theory argues that people voluntarily migrate because it is in their best interest to do so; people move from low- to high-income areas, from areas with high density to low density areas. In essence, this theory implies that there are “push factors” that compel people to leave their home countries, and “pull factors” in the receiving countries that attract them. This is an individualistic, ahistorical, and very single-dimensional view of migration.

Historical-Structural – This approach is based on Marxist political economy and on world systems theory. It holds that migratory movements are a way of mobilizing cheap labor for capital and are the result of the unequal distribution of economic and political power between DCs and LDCs. Unlike the Neo-Classical approach, the Historical-Structural approach holds that migration is not a voluntary phenomenon, but rather a process through which capital recruits labor. It also argues that migration is a way for DCs to maintain their hegemonic dominance over periphery economies. This theory of migration has been criticized for attributing capital an omnipotent quality and not paying sufficient attention to individuals’ personal motivation. Migration System – This is a multi-disciplinary approach that studies different factors that may influence migration: economic, cultural, social, political, and environmental. This approach examines the factors in both ends of the migration flows, and suggests that migratory movements arise from pre-existing links between source and receiving countries. The links may be based on colonization, political influence, trade, investment, or cultural ties. |

Source: Summarized from Castle and Miller (2003), pg. 22-29; also see Graham (1996) and Pedraza (1999)

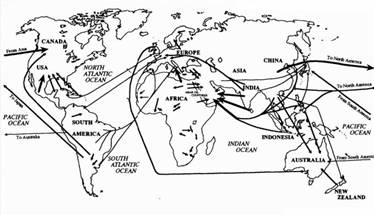

These theories portray migration as the result of different phenomena. The Neo-Classical theory is the most widely use. For example, Addy, et al, (2003) argue that the increase in international migratory movement is a reflection of the worsening economic situation in the source countries (push factors) and increasing job opportunities in the destination countries (pull factors). To a large extent, the intensifying international migration over the last few decades is a result “of widening income inequalities, (low social mobility within source countries,) and the growth in employment-related migration caused by labor shortages in the service sector (notably in domestic services and the health care sectors), the construction industry and in the agricultural sectors of many migrant destination countries” (Addy, et al, 2003: pg. 4). Kapur (2003) also argues that people migrate because of economic reasons. He holds that economic and financial crises in LDCs over the past two decades are the major factors in the increase in the flow migrants to DCs. Other major forms of migratory movements include refugees, asylum seekers, students, and skilled and professional labor. Figure 1 depicts the migratory flows since the early 1970s. It clearly shows that, for the most part, Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia, U.S., and European countries are the major destinations for international migrants.

Figure 1: Global Migratory Movements from 1973

Note: Arrow dimensions give only rough indication of migration flow. |

In the Dominican and U.S. context, DR is one of the largest sources of migrants to the US. “From 1988 to 1998, a total of 401,646 Dominicans were admitted to the US. This figure is almost twice the total admitted from any other country in the Caribbean, including Jamaica (213, 308), Haiti (211, 657), Cuba (184, 147)” (Castro and Boswell, 2002: pg. 1). Overall, the DR is the third largest source of immigrants from LAC to the US: after Mexico (6.68 million), Cuba (.98 million), DR (.92 million) (Homeland Security, 2004: pg. 14). Figure 2 shows Dominican migration to the US since the 1930s. It shows that starting in the 1960s, Dominican migration to the U.S. mushroomed. This is doubtless in part due to the 1965 changes to U.S. immigration policies (Graham, 1996; Pedraza, 1999); at the same time, however, the increase in migration may also reflect the political and economic problems that have plagued the DR, and the constant U.S. involvement in Dominican affairs- starting with a U.S. sponsored coup in 1963 and eventual U.S. occupation in 1965 (Graham, 1996) [3].

Figure 2: Dominicans Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status in the US (1930-2005)

|

The increase in Dominican migration to the U.S. is part of the most recent wave of mass-immigration to the U.S. Many scholars claim that the U.S. has had four major waves of migration. “The first wave consisted of Northwest Europeans who immigrated up to the Mid-nineteenth century; the second consisted of southern and eastern Europeans, at the end of the ninetieth century and beginning of twentieth; the third is the movement from the south to the North of Black Americans, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans, precipitated by two world wars; and the fourth wave, from 1965 and ongoing, comprises immigrants mostly from Latin America and Asia” (Pedraza, 1999: 379). Graham (1996: 19-20) has a similar categorization of migration waves [4]. The key impetus of the current wave of immigration into the U.S. were the changes introduced by the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which abolished the series of strict, eugenic quotas based on country of origin. These quotas attempted to maintain the “original” racial makeup of the U.S. back in the beginning of the nineteenth century. The quotas favored migration form Northern Europe, and severely restricted migration from the global south [5]. The DR is among the many Third-World countries that have “benefited” [6] from the post-1965 immigration policies.

Dominican migrants living in the U.S. have maintained close ties with their home-country. Many of their social, cultural, economic and political practices can be considered transnational- that is, they involve cross-border activities such as travel, religious practices, communication, education, business investments, political activism, monetary remittances, funding development projects, and following the news from the home-country. These are only a few of the many sustained practices that constitute the transnational life of Dominican migrants (Smith, 2005; Graham, 1996; Guarnizo, 1998; Itzigsohn, 2000). For purposes of this paper, I will briefly provide an overview of remittances as a typical transnational process in which Dominican migrants engage in. I hold that remittances are a good indicator for gauging transnational practices since sending remittances is one o of the more involved transnational processes; more than sending emails, reading a newspaper, or making phone calls. In addition to being an involved process, economic exchanges are important to creating and maintaining transnational practices and ties. “The act of providing economic support to families and to communities of origin allows migrants to maintain a role in the affairs of the sending country, at least at a micro-level… Migrants abroad become constituted formally or informally as a social group with interests and roles to play in the sending country despite or precisely because of their residence abroad” (Graham, 1996: 50). Thus I claim that remittances can serve as an indicator for maintained transnational practices and ties with the home-country.

The IDB (2004b) estimates that 70 percent of Dominican migrants remit money back to their relatives and friends in the DR; that is 1.4 million remitters- 710,000 from the US, 440,000 from Europe, 180,000 from Puerto Rico and 70,000 from the rest of the world. In the US alone, 71 percent of the almost 1 million Dominican migrants send remittances on a regular basis (Bendixen, 2004; Home Land Security, 2004). The total amount of remittances to the DR in 2005 was US$2.5 billion, which made up 9 percent of the GDP, US$28.3 billion. This flow of foreign exchange is important for the families that receive remittances because it allows them to maintain consumption levels, access education and health services, and/or improve their housing; it is also very important for the national economy in that it helps promote economic activity and funds the purchase of imports. Thus, as can be seen from the figures provided by the IDB, a vast majority of Dominican migrants, including me, send remittances to DR, and subsequently maintain close ties to their home-country.

In the political realm, Dominican migrants have historically been politically engaged in Dominican politics. In the 1940s, Dominican migrants in New York established one of the major Dominican political parties, Partido Revolucionario Dominicano (PRD) (Jimenez Polanco, 1999; Lozano, 2002; Graham, 1996; Guarnizo, 1998). And throughout the years, Dominican migrants have maintained their party affiliation and continued financially supporting their parties from abroad (Guarnizo, 1998; Graham, 1996). Moreover, since constitutional and electoral reforms in the mid 1990s, Dominican citizens living abroad can actually now vote in Dominican elections from abroad. This is apparent from the anecdote I presented at the start of this paper.

These transnational practices and ties problematize traditional nationally-based theories of migration and political incorporation. These models of political incorporation of migrants focus exclusively on host-country incorporation, and they neglect migrant’s transnational political, economic, and social ties and practices (Faist, 2000: 201). They are typically combined with Neo-Classical theories of migration, and use income and wages to measure immigrants’ incorporation into the host-country. Culturally, these nationally-based incorporation models use “fluency in receiving country’s dominant language and degree of interaction with non-immigrant groups (as) measures of incorporation into the ‘new’ society” (Graham, 1996: 6). Moreover, these models claim that as incorporation into the host-country occurs the links to the home-country recede: in other words, they see political and cultural incorporation in the home- and host- countries as a zero-sum game, one has to decrease or stagnate in order for the other to increase or be maintained. This logic is associated with assimilation theories. Like territorially-based citizenship theories, assimilation theories contend that citizenship is an exclusive identity in a single national-state, and that “gradually immigrants do away with the cultural baggage transported from the emigration country. As immigrants continue to embark upon the member-ships of the perhaps multiple rivers and riverains of the receiving country, the logical end point (according to assimilation theories) is single nation-state citizenship, characterized by a dominant and unitary political cultural core” (Faist, 2000: 204).

Another major theory of migrant incorporation is the multicultural theory. Pluralist or multicultural models are more flexible than assimilation models. They contend that cultural assimilation is not necessarily the end-point of migration. These theories allows for migrants to hold on to the cultural identity from their home-country. Many immigrant groups retain their cultural values and identities and settle into a particular space within the host-country’s society where they can hold onto their distinct values, practices, and identities. However, “like proponents of assimilation theory, they regard adaptation exclusively in the container space of nation-states,” they disregard transnational ties and practices (Faist, 2000: 208). What’s more, politically they contend that migrants will lose their political links with their home-country, as they incorporate into the politics their host-country. Thus, like assimilation theories, the multicultural theories are nation-based, see political incorporation as a zero-sum game, and contend that the ultimate point of migrant is for migrants to incorporate into the host-country.

The theoretical and methodological implications of these theories are very significant on the way migration, political incorporation, and identity is studied. Since these nationally-based theories focus exclusively on the host-country, treat assimilation as the goal of migrants and the end of the immigration process, and contend that citizenship is a territorially-based identity, then studies of immigration that use an assimilation or multicultural theoretical framework will fall short of examining the many aspects of the transnational lives of migrants (Smith, 2005: 7; Faist, 2000: 209; Graham, 1996: 7).

Transnational models of migration, political incorporation, and national identity take a broader approach to studying migration and political incorporation. Unlike national assimilation models or even multicultural models, the transnational approach includes contextual and structural factors in both the home- and host- countries. Guarnizo’s (1998) study of Dominican and Mexican migration and their transnational political practices and identities is an example of a transnational model. In this article, Guarnizo (1998) describes the many ways that migrants partake in economic, cultural, and political practices in both the home- and host- countries and the institutional context that has allowed and encouraged such transnational practices to blossom. For Guarnizo (1998), transnationalism is “a series of economic, sociocultural, and political practices and discourses which transcend the confines of the territorially bounded jurisdiction of the nation-state and are an inherent part of the habitual lives of those involved” (pg. 52). Guarnizo looks at the political and civil society organizations that are engaged in transnational processes, and concludes that the current moment of migration and political transnationalism goes beyond conventional theories of migration that are focused on assimilation.

This view is shared by both Graham (1996) and Smith (2005). Smith (2005) says that “most transnationalists avoid the concept of assimilation, which they conceive of” as conflicting with the transnational reality of immigrants (p. 7). Smith (2005) argues, that proponents of assimilation theories claim that loyalties to home countries will decrease with time, but that the transnational ties and practices that persist from one generation to the next of immigrants obviously points to a more complex relationship between assimilation and transnational life. This complexity is analyzed by Pamela Graham’s (1996) case-study of “simultaneous” political incorporation of Dominican migrants in the political systems of their home- and host- countries. To study how Dominican migrants increased their political engagement in both American and Dominican politics, Graham looked at the political mobilization of migrant groups to pressure city and state officials in New York to create a political district that would allow for Dominicans in New York to have representatives in the city assembly and state legislature. Concurrently with these efforts in NY, migrant organizations were also articulating demands by the Dominican migrant community for civil and political rights in the DR for Dominicans living abroad, particularly dual-citizenship and the right to vote. Migrant groups lobbied both American and Dominican political leaders to realize these goals (Guarnizo, 1998; Graham, 1996; Itzigsohn, 2000). Graham (1996) looks at these efforts for political incorporation in the home- and host- countries as an example of how “conventional concepts of immigration based on neoclassical economic theory” and nationally-based theories of assimilation and multicultural-citizenship are unable to account for the continued, circular dynamics of migration and transnational ties and practices (p. 31) [7].

In addition to challenging concepts of migration and political incorporation, the transnational perspective on migration also presents a dilemma to concepts of citizenship and identity based on the nation-state. As stated above, citizenship is a concept of membership and identity that represents a “set of rights, duties, roles, and identities” linked to the nation-state (Koopmans, 1999: 654). Soysal (1994) and Jacobson (1996) argue that transnational migration is de-linking, or eroding, the traditional connection between national citizenship and the rights and duties embodied in being a member of a political community. In a sense, they argue that migration presents a “postnational” challenge to citizenship. They base this critique on the fact that “as rights have come to be predicated on residency, not citizen status, the distinction between ‘citizen’ and ‘alien’ has eroded” (Jacobson, 1996: 8-9) [8]. But more to the point of my paper, migrants’ transnational practices and ties, their political involvement in multiple political arenas, and the multi-membership introduced by dual-citizenship laws have transcended the traditional territory-based concepts of citizenship. These changes have developed what Pedraza (1999), Laguerre (1998), and Foner (1997) have labeled diasporic citizenship. Diasporic citizenship is “a set of practices that a person is engaged in, and a set of rights acquired or appropriated, that cross nation-state boundaries and that indicate membership in at least two nation states” (Laguerre, 1998: 190). Nancy Foner (1997) argues that Dominicans’ political involvement in Dominican politics is a clear example of diasporic citizenship in practice. “In the last Dominican elections (1996 at the time), many Dominicans residing in New York quickly flew to the island to vote. In future elections, the trip will be unnecessary because electoral reforms ensure that they can vote while remaining in New York. This gives the Diaspora (whether Haitian, Dominican, soon Mexican) a role in homeland politics that is much larger than ever before” (Pedraza, 1999: 380). In other words, these scholars argue that the extension of political duties and rights beyond national territories is removing “citizenship” from a necessary location within the nation-state. This is a direct challenge to conventional concepts of citizenship that locate political rights to a given nation-state territory, and that claim that citizenship to a nation-state is an exclusive identity that prohibits individuals from having two or more citizenships (Faist, 2000: 201).

Despite informal transnational processes and ties, only states are able to delimit the borders of formal membership in their political community and the rights and duties that accompany membership. I turn now to exploring some of the mechanisms by which states are expanding citizenship rights and negotiating the boundaries of national identity and political participation. According to Faist (2000), formal dual membership comes in two forms: the first is dual citizenship and the second is dual nationality. The first grants the individual full rights and duties in two, or more, countries. The rights under the second are more restricted than under the first. “For example, holders of Declaration of Mexican Nationality IDs are not able to vote or hold political office in Mexico, or to serve in the Mexican Armed Forces” (p. 202). Dual nationality, as in the case of Mexico, usually provides some enhanced treatment vis-à-vis property-rights and inheritance laws, but it does not grant the full rights and duties of citizens.

In the last decade, many Latin American and Caribbean countries have been systematically opening their political system to the participation of their citizens living abroad. These expansions of political rights included the allowance of dual-citizenship, the ability for migrants to vote in the national elections of the home-country and contribute to political campaigns, ability for migrants to join political tickets, and the latest overture has been actual representation for migrant communities in national legislative bodies. Jose Itzigsohn’s (2000) article on “Immigration and Boundaries of Citizenship” is a comparative historical attempt at identifying the institutional factors that have shaped migrants’ transnational politics. Itzigsohn (2000) focuses on “the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and El Salvador and argues that they share an institutional pattern of transnational politics in which there are three main actors: the state apparatus of the country of origin; the political parties of the country of origin; and migrant organizations in the country of reception” (pg. 1126). Itzigsohn (2000), along with Graham (1996) and Guarnizo (1998), argues that these changes in formal membership were the result of continued negotiations between immigrant groups making claims on political institutions on behave of migrants living abroad, and the state and political parties trying to play on their migrants’ loyalty in order to maintain the continued flow of economic and political resources in the form of remittances, campaign financing, and investment in private enterprises and development project.

Guarnizo (1998) and Itzigsohn (2000) go as far as to claim that immigrant organizations abroad were instrumental in getting the formal political inclusion of migrants living abroad. “Until recently, the attitude of the Dominican state regarding the state and conditions of the Dominican population abroad was marked by neglect and disinterest… Until 1996, there had never been any governmental agency or official program designed to address Dominican migrants’ concerns, or even to facilitate or encourage the repatriation of capital and/or people to the island” (Guarnizo, 1998: 68). The Dominican migrants’ struggle for inclusion, Guarnizo (1998) argues, was a bottom up approach; in other words, the traditional power-brokers and political stakeholders were content with the status quo of having Dominicans abroad remit funds and be marginally or symbolically involved in Dominican politics; but immigrant organizations, as described by Graham (1996) and Itzigsohn (2000), organized the Dominican community abroad and presented a united front against formal political institutions in the DR. The inclusion of Dominicans abroad was thus the result of grassroots efforts led by immigrant organizations. Changes to the Dominican constitution occurred in 1994.

In addition to changes in formal citizenship rights, in 1996 Leonel Fernandez, a transnational migrant who lived in New York during his childhood, was elected president, and efforts to include Dominicans abroad increased. Under Fernandez’s headship, the DR adopted symbolic initiatives to include Dominicans abroad. Dominican migrants started to be called Dominicans residing abroad [9], bureaucratic procedures were relaxed to facilitate investment in the DR, importing of goods into the DR, and resettlement back in the DR by Dominicans residing abroad. Moreover, Dominicans residing abroad were labeled national heroes and recognized as a legitimate part of the Dominican nation. The most recent gestures of inclusion are additional proposed changes to the Dominican constitution that would allow Dominicans residing abroad to be elected as representatives of the “Diaspora” in congress (Guarnizo, 1998: 75). This means that a congress would potentially have a representative from Washington Heights, NY or Lawrence, MA representing the interests of Dominicans living abroad. To this end, the current debates to reform the constitution have included Dominicans living abroad. President Fernandez himself has held several town-hall meetings in New York, Boston, and Providence to build political support among the Diaspora for his suggested constitutional reforms. These apparently trivial discursive changes, presidential visits, and political gestures have “the powerful effect of recognizing migrants as active and present members of the nation, a recognition that migrant leaders have sought for a long time” (Guarnizo, 1998: 75). Of course, these institutional changes and “official” overtones are simply playing catch-up to already existing transnational practices and identities which have already expanded the boundaries of the Dominican imagined community.

Up to this point, I have attempted to establish that migration and political transnationalism is expanding the concept of citizenship and presenting a dilemma to conventional theories of citizenship, migration and political incorporation. The continued transnational cultural, economic, and political practices, along with the informal and formal expansion of citizenship rights and duties have problematized nationally-based theories. A transnational approach is needed to analyze the political reality of migrants (Faist, 2000; Graham, 1996; Smith 2005). The emerging literature on migration and political transnationalism addresses the shortfalls in conventional theories of migration, citizenship, and political incorporation. It provides a broad scope to conduct analysis of these transnational political realities. I find that the literature on migration and political transnationalism focuses on three aspects of how migration is transnationalizing politics: 1) simultaneous incorporation of migrants in the politics of both home- and host- countries; 2) institutional changes in the home- and host- states and political parties to “open” the political system to migrants and allow transnational practices; 3) and the ways the home-countries have become dependent on the financial and political capital remitted to them by their Diaspora (Smith, 2006; Smith and Guarnizo, 1997; Itzigsohn, 2000 and 1995; Pedraza, 1999; Goldring, 2002). These research foci are evident in some of the works I have presented above regarding Dominican migrants (e.g. Itzigsohn, 2000). They have expanded the theoretical approach to studying issues of citizenship, migration, and political incorporation; however, the existing literature on migration and political transnationalism pays little attention to non-migrants who are linked to migration via remittances or cultural exchanges.

For example, scholars working on Dominican migration and political transnationalism have studied the incorporation of Dominican migrants into Dominican and American politics by the extension of electoral rights, allowing dual-citizenship, the creation of immigrant groups in the host-countries, and the expansion of political activities by political parties. For instance, Sagas (2004), Itzigsohn (2000), and Graham (1996) describe how Dominican political leaders actively campaign and solicit funds in Dominican communities outside the DR. In exchange for support, the government and political institutions are willing to incorporate the Dominican Diaspora into Dominican politics; this is the transnationalization of Dominican politics (Itzigsohn, 2000; Sagas, 2004). Despite this transnational approach, no effort has been made to understand how migration is affecting the political attitudes and participation of non-migrating individuals. As a consequence, little, if anything, is known about this facet of migration and political transnationalism.

For example, take non-migrating individuals who receive remittances. It is reasonable to aver that remittances, through their proclaimed economic, social, and cultural effects, have an effect on recipients’ political views and expectations of local political processes, institutions, and actors, and the type and amount of political participation they engage in. Similarly, it is also reasonable to presume that the exogenous nature of remittances, in that it differs from self-generated economic wellbeing, may present a dilemma to the conventional wealth-democracy theories that argue that as individuals’ income improve their demands to be included in political decision making increase. In other words, because remittances are exogenous to the local political and economic situation, and because they may increase recipients’ desire to migrate, recipients may become disinterested in local politics and develop an orientation to the “north”. The migration and political transnationalism literature has not even considered these issues. There is a complete lack of insight into these aspects of political transnationalism. If we assume that remittances increase recipients economic wellbeing, and also that they have an effect on recipients’ political attitudes and participation, then two key questions arise: 1) what are the mechanisms by which remittances affect recipients’ political attitudes and participation? and 2) do recipients’ political views, interests, and participation differ from non-recipients’? These are questions that have gone unaddressed by the scholars.

The transnational approach to studying migration, political incorporation, and citizenship has expanded our knowledge, improved our research methods, and addressed many of the shortfalls in conventional theories of citizenship and migration, but the approach needs continued development. A transnational approach should not only focus on migrants, the state, and political/civil society organizations (immigrant groups, political parties), it should include the effects of migration on non-migrating individuals who are linked to migration through monetary and cultural exchanges, like remittances. By taking this comprehensive tactic, the transnational approach to migration and citizenship will truly increase our understanding of migration and political transnationalism.

References

Addy, David Nii, Wijkstrom, and Thouez, Colleen (2003): “Migrant Remittances – Country of Origin Experiences”, International Migration Policy Programme, London, UK. http://www.livelihoods.org/hot_topics/docs/REMITPAPER.doc (4/11/05)

Baubock, Rainer (2003): “reinventing Urban Citizenship”, in Citizenship Studies, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2003, pp. 139-160

Bendixen & Associates (2004): “Remittances and the Dominican Republic”, IDB, Washington DC, http://www.iadborg/mif/v2/files/bendixen_NYNov04.pdf (4/21/05)

Black, Jan Knippers (1986): The Dominican Republic: Politics and Development in an Unsovereign State, Boston, MA: Allen & Unwin, Ltd.

Castles, Stephen and Miller, Mark (2003): The Age of Migration, The Guilford Press, New York, NY.

Castro, Max and Boswell, Thomas (2002): “The Dominican Diaspora Revisited: Dominicans and Dominican-Americans in a New Century”, The North-South Agenda, University of Miami, Miami, FL http://www.ciaonet.org/wps/cam03/cam03.pdf (4/21/03)

Dagger, Richard (2002): “Republican Citizenship”, in Engin F Isin, Bryan S. Turner, eds, Handbook of Citizenship Studies, London, UK: Sage Publications Inc., pp. 145-157

Dominican Today (2007): “Dominican Cedula, Birth certificate to be issued in the Airports”, March 7th, 2007, Dominican Today http://www.dominicantoday.com/app/article.aspx?is=22987

Faist, Thomas (2000): “Transnationalization in International Migration: Implications for the Study of Citizenship and Culture”, in Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 23, No. 2, March 2000, pp. 189-222

Foner, Nancy (1997): “What’s New About Transnationalism? New York Immigrants Today and at the Turn of the Century”, in Diaspora, Vol. 6, pp. 355-376

Goldring, Luin (2002): “The Mexican State and Transmigrant Organizations: Negotiatinve Boundaries of Membership and Participation”, Latin American Research Review, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2002, pp. 55-99

Graham, Pamela M. (1996): “Re-imagining the Nation and Defining the District: The Simultaneous Political Inforporation of Dominican Transnational Migrants”, 1996 Dissertation, University of North Carolina

Guarnizo, Luis Eduardo (1998): “The Rise of Transnational Social Formations: Mexican and Dominican State Responses to Transnational Migration”, in Political Power and Social Theory, Vol. 12, pp. 45-94

IDB (2006): “Latin America and the Caribbean to receive more than $60 billion in remittances in 2006, IDB fund estimates”, IDB, press release, September 13, 2006 http://www.iadb.org/news

IDB (2004a): “Sending Money Home: Remittances to Latin America from the US, 2004”, IDB, Washington DC. map2004survey.pdf (4/11/05)

Itzigsohn, Jose (2000): “Immigration and the Boundaries of Citizenship: The Institutions of Immigrants’ Political Transnationalism”, International Migration Review, Vol. 34, No. 4, Winter, 2000, pp. 1126-1154.

Itzigsohn, Jose (1995): “Migrant Remittances, Labor Markets, and Household Strategies: A Comparative Analysis of Low-Income Household Strategies in the Caribbean Basin”, Social Forces, Vol. 74, No. 2, December 1995, pp. 633-655

Jacobson, David (1996): Rights Across Borders: Immigration and the Decline of Citizenship, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jiménez Polanco, Jacqueline (1999): Los partidos políticos en la República Dominicana: Actividad electoral y desarrollo organizativo, Santo Domingo, RD: FLACSO

Kapur, Devesh (2003): “Remittances: The New Development Mantra?”, G24, Washington DC. http://www.g24.org/dkapugva.pdf (4/12/05)

Koopmans, Ruud and Statham, Paul (1999): “Challenging the Liberal Nation-State? Postnationalism, Multiculturalism, and the Collective Claims Making of Migrants and Ethnic Minorities in Britain and Germany”, AJS, Volumbe 105, No. 3, November 1999, pp. 652-696

Laguerre, Michel S. (1998): Diasporatic Citizenship: Haitian Americans in Transnational America, New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press

Levitt, Peggy (1999): "Social Remittances: A Local-Level, Migration-Driven Form of Cultural Diffusion", International Migration Review, Vol. 32(124): Winter, 1999. Pp. 926-949

Levitt, Peggy (2006): “Social Remittances - Culture As A Development Tool”, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: INSTRAW, Peggy_Levitt.pdf (9/12/06)

Lozano, Wilfredo (2002): Despues de los Caudillos, Santo Domingo, RD: FLACSO

Marshall, T.H. (1998): “Citizenship and Social Class”, in Gershon Safir (ed) The Citizenship Debate: A Reader, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 93-112

Meyers, Deborah (1998): “Migrant Remittances to Latin America: Reviewing the Literature”, Inter-American Dialogue, http://www.thedialogue.org/publications/meyers.html

ONE (2006): “Población que reciben remesas del exterior por rango de dinero que reciben mensualmente, según región, provincia, municipio, distrito municipal, sección, bario o paraje”, Santo Domingo, RD: ONE

Pedraza, Silvia (1999): “Assimilation or Diasporic Citizenship”, in Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 28, No. 4, July 1999, pp. 377-381

Sagas, Ernesto and Molina, Sintia E. (2004): Dominican Migration – Transnational Perspectives, Tampa, FL: University of Florida Press

Schuck, Peter H. (2002): “Liberal Citizenship”, in Engin F Isin, Bryan S. Turner, eds, Handbook of Citizenship Studies, London, UK: Sage Publications Inc., pp. 131-144

Smith, M. Peter (2003): “Transnationalism, the State, and the Extraterritorial Citizen”, in Politics & Society, Vol. 31, No. 4, December 2003, p. 467-502

Smith, M. Peter and Guarnizo, Luis Eduardo (1997): Transnationalism from Below, Transaction Publishers

Smith, Robert (2006): Mexican New York, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

Smith, Rogers M. (2001): “Citizenship and the Politics of People-Building”, in Citizenship Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2001, pp. 73-96

Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoglu (1994): Limits of Citizenship. Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe, University of Chicago Press.

Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoglu (1997): “Changing Parameters of Citizenship and Claims-Making: Organized Islam in European Public Spheres”, in Theory and Society, Vol. 26, pp. 509-527

Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoglu (1998): “Toward a Postnational Model of Membership”, pp. 189-220 in Gershon Shafir, ed. The Citizenship Debates. A Reader, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Stychin, Carl (2001): “Civil Solidarity or Fragmented Identities: The Politics of Sexuality and Citizenship in France”, in Social and Legal Studies, Vol. 10, No. 3, September 2001, pp. 347-376

Suki, Lenora (2004): “Financial Institutions and the Remittances Market in the Dominican Republic”, The Earth Institute, Columbia University, New York, NY http://www.iadb.org/mif/v2/files/Suki_NYNov04.pdf (4/21/05)

Turner, Bryan S. (1990): “Outline of a Theory of Citizenship”, in Sociology, Vol. 24, No. 2, May 1990, pp. 189-217

Walzer, Michael (1989): “Citizenship”, in Terence Ball, John Farr and R.L. Hanson (eds.) Political Innovation and Conceptual Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 211-219

[1] The term “Dominicans residing abroad” is part of the recent inclusive discourse to incorporate for Dominican transnational migrants into the DR’s politics and society. I discuss this further below.

[2] I chose the Dominican Republic (DR) for two important reasons: compatibility with both Latin American and Caribbean countries; and that in the last decade the Dominican state has actively promoted the incorporation of its transnational migrants. Firstly, as Black (1986) and Betances (1995) cogently argue, the DR is a bridge between the Latin America and the Caribbean. “It is a potential source of insight into problems facing many other countries, especially those of Latin America and the Caribbean” (Black, 1986: 1). It also typifies the democratization and neo-liberal waves that occurred in LAC since the 1980s (Jimenez Polanco, 1999; Batences, 1995; Lozano, 2002). Secondly, the DR’s recent efforts to incorporate its transnational migrants make it a crucial case, a la Harry Eckstein, to study the relationship between migration, political transnationalism, the expansion of citizenship rights and duties beyond the nation-state borders.

[3] This Historical-Structural argument is not uncommon is studies of Dominican migration. See Grasmuck, Sherri and Pessar, Patricia R. (1991): Between Two Island, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

[4] She only focuses on the 20th century.

[5] For an overview of immigration policies, and the changes introduced in 1965, see Mae Ngai’s (1999) “The Architecture of Race in American Immigration Law: A Reexamination of the Immigration Act of 1924”, Journal of American History, 86, June 1999: p. 67-92. And David M. Reimers (1983): “An Unintended Reform: The 1965 Immigration Act and Third World Immigration to the United States,” Journal of Immigration History, Fall 1983.

[6] I put the word benefited in quotes, because there is a large debate whether immigration is actually beneficial to labor exporting countries. For more details see Alejandro Portes (1978): “Migration and Underdevelopment,” Politics and Society, 8, 1978, 1-48.

[7] Smith (2005), Pedraza (1999), and Faist (2000) are some of the other scholars that also provide similar criticisms against nationally-based theories of migration and political incorporation.

[8] Even these views are based on assimilation and multicultural theories of migration and political incorporation. They see migration as a challenge to citizenship not because of transnational practices, but rather because denizens enjoy similar benefits to citizens.

[9] instead of Absent Dominicans or Dominican Immigrants.